You may be amazed to know when some of the most important concepts to inform visual communication were discovered. Our discipline just wasn’t mature enough to be sitting at the same table with some of these brilliant thinkers. And some of these concepts have been virtually lost – lost in our current infatuation with the present.

This story begins in Second World War (1939–1945), which necessitated the development of new ideas, from discoveries in physics, to radar, signal encryption and communication technologies. After the war, it took a little while to unpack the thoughts people had developed – to realign their discoveries with the new world they faced, and to put these ideas to work.

So in 1948, Claude Shannon did exactly that, and revolutionized the way humans thought about information. During the war, Shannon had worked developing antiaircraft gun guidance systems, and later, moved into cryptology. After the war, Shannon worked for Bell Labs, researching communication technology [1].

In A Mathematical Theory of Communication (1948), Claude Shannon introduced the world to information theory. To Shannon, information was simply binary stuff that was sent from one computer to another [2]. The meaning of the information being transmitted was irrelevant to Shannon, which resulted in an important clarification written the following year by his colleague, Warren Weaver.

“The word information, in this theory, is used in a special sense that must not be confused with its ordinary usage. In particular, information must not be confused with meaning” [3].

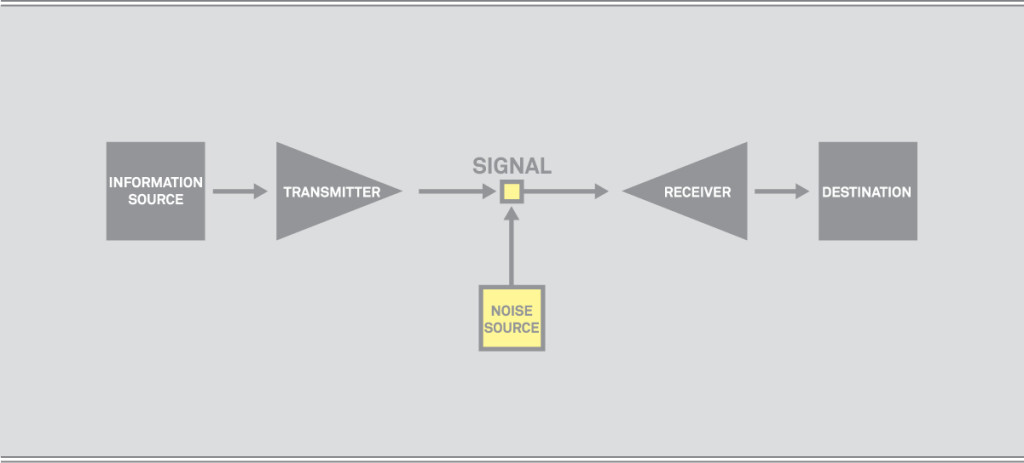

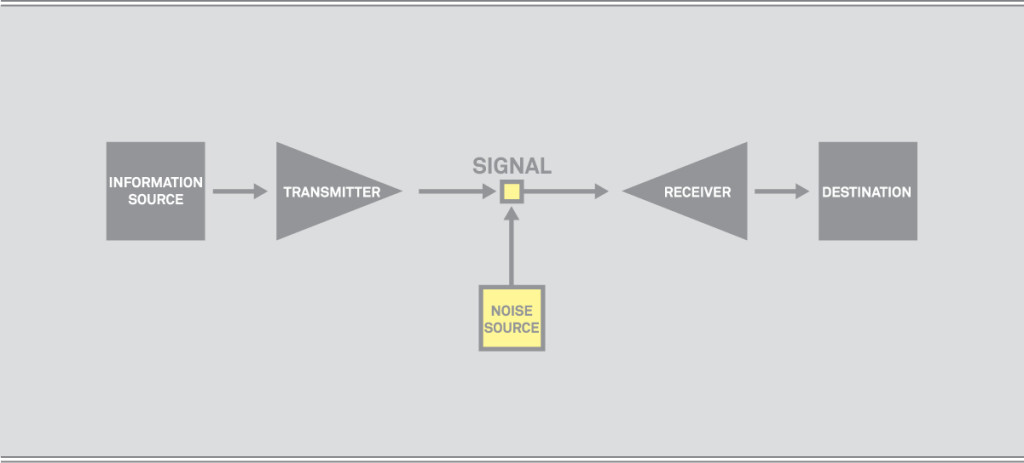

Weaver knew that Shannon’s communication diagram, shown below, described the transfer of raw data, not necessarily having meaning. Shannon was only concerned with the accurate transfer of binary stuff.

Figure 1. Shannon’s basic communication system.

(adapted from Shannon, 1948, p. 381)

The figure above describes the fundamental elements of Shannon’s communication system. It is easily understood by comparing it to a telephone system, with a message sender, the transmitter, the telephone signal, the receiver and a listener [3]. It can also be related to a basic visual communication system.

But what I want to call your attention to, if you haven’t already noticed, is that the diagram has a noise source that affects the signal. Shannon suggests that noise is an undesirable, yet persistent component of communication systems. This concept of noise within communication channel became a focus of interest over the following decade, explored through various disciplines. The following two examples taken from the disciplines of fine art painting and music composition illustrate just two similar explorations.

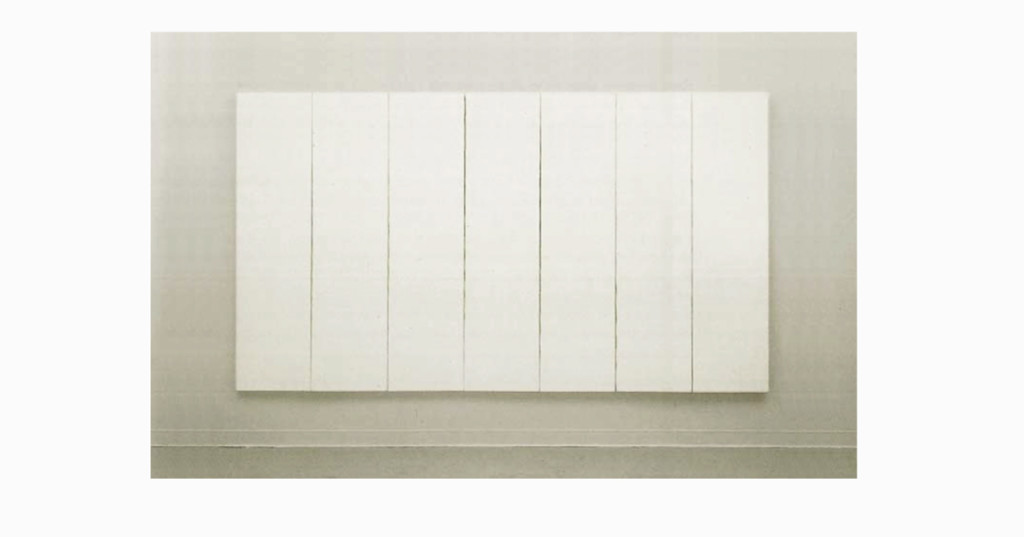

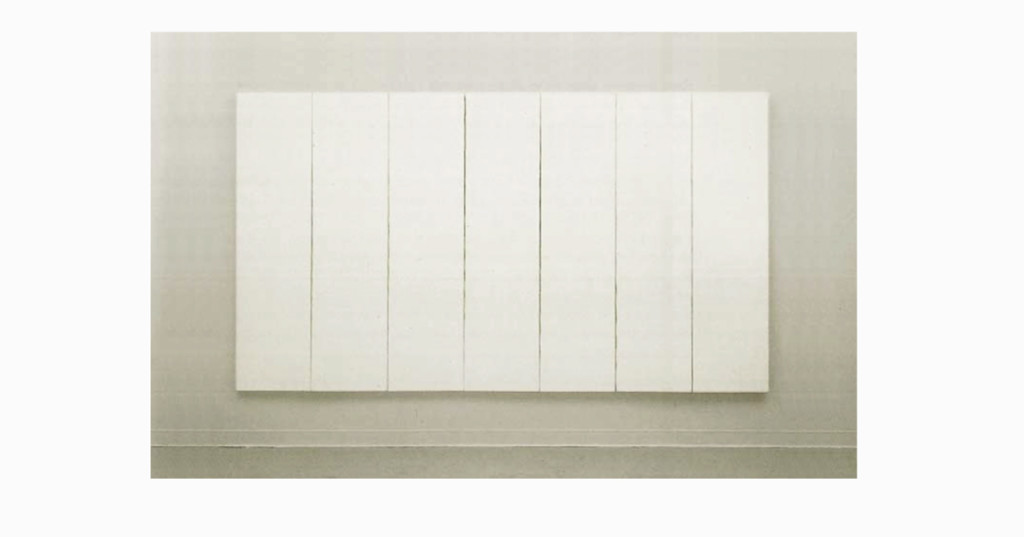

Robert Rauschenberg’s white paintings:

In 1951 Robert Rauschenberg painted a series of purely white paintings, exploring the ambient effects of the surrounding light sources and reflective surfaces on his paintings. Basically the blank canvasses exposed the visual noise on any canvass’ surface.

Figure 2. One of Rauschenberg’s White Paintings (Rauschenberg, 1951).

Retrieved from http://www.studyblue.com)

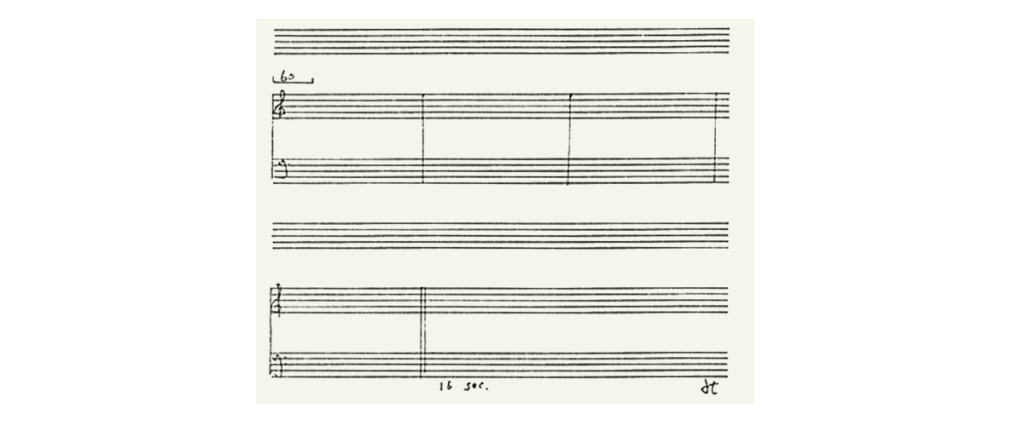

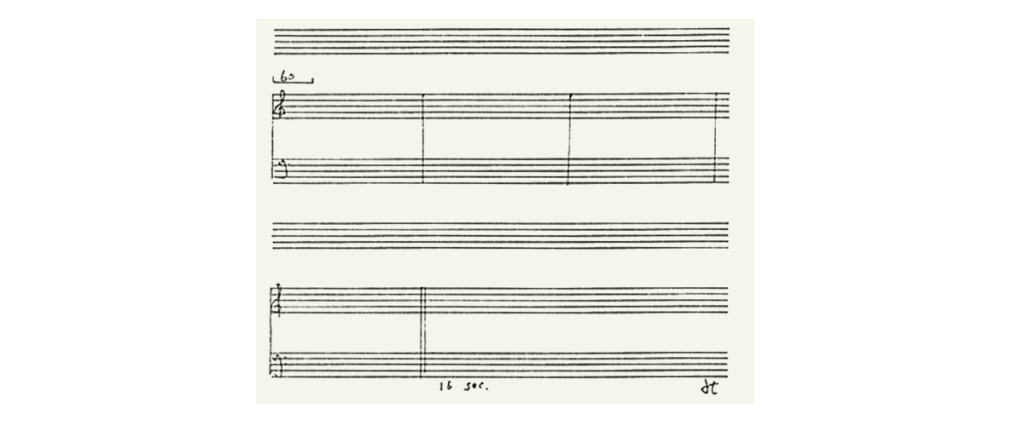

John Cage’s 4’33”: 1952 brought John Cage’s 4’33” – a piece of music (written to be performed by any group of instruments) in which the performers stay silent for 4 minutes and 33 seconds. Actually, Cage’s point was to explore the noise behind the music, created by the immediate environment, audience, stage musicians, and external influences. Cage framed the noise within a 4 minute and 33 second time frame (go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zY7UK-6aaNA).

Figure 3. Part of Cage’s score for 4’33” (Cage, 1952).

Retrieved from http://smithsonianmag.com)

1954: SCHRAMM AND FIELDS OF EXPERIENCE

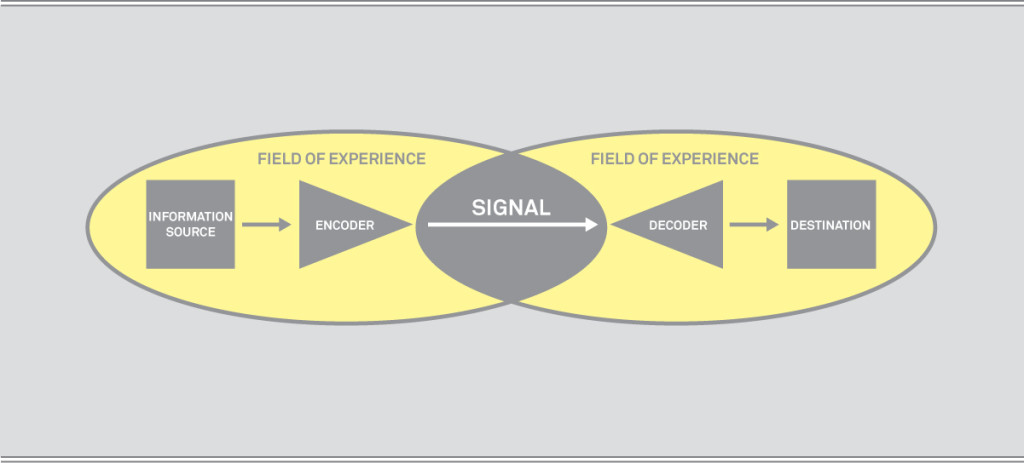

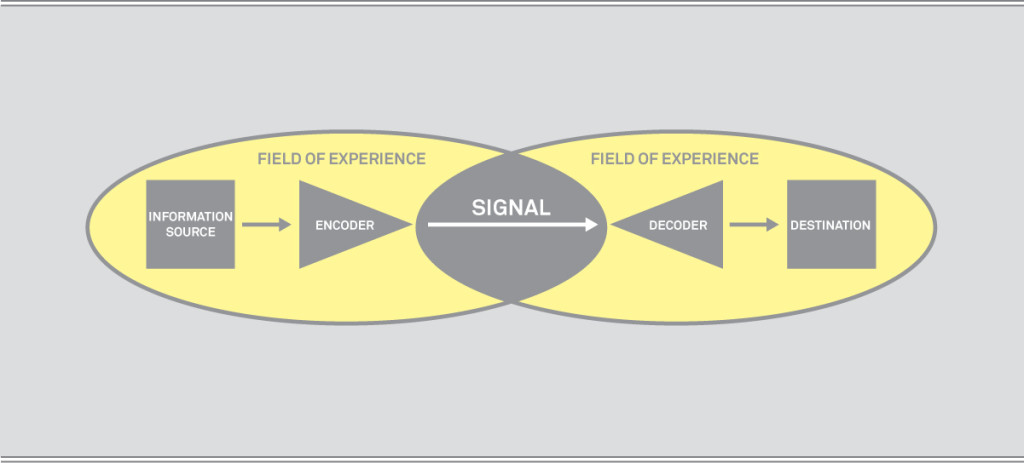

Wilbur Schramm is often called the father of Communication Studies. In his 1954 book, The process and effects of mass communication, Schramm integrated the transfer of meaningful information into Shannon’s diagram of 1948.

Figure 4. Schramm’s field of experience diagram.

(adapted from Schramm, 1954, p. 6).

Figure 4 shows that meaning can be transferred through a Shannon-like system, yet Schramm shows that the sender and receiver’s signal (message) only has meaning where the fields of experience of the communicators overlap. The non-common parts of their fields of experience (experience = culture, language, jargon, known symbols etc.) is not communicable between them and is therefore noise. “This is the difficulty we face when a non-science-trained person tries to read Einstein, or when we try to communicate with another culture much different from ours” [4].

1958: CHANNEL NOISE, CODE NOISE

Charles Hockett was interested in communication from a different perspective – that of linguistics – through which he theorized a similar concept to Schramm’s idea of fields of interest. In 1958, a decade after Shannon, the American linguist described the set of common terms between any linguistic groups that regularly communicate, as their common core. Any of the terms from the common core are mutually meaningful, but if any of the speakers resort to using elements of their vocabulary outside their mutual common core, they produce what Hockett called code noise [5].

Hockett also coined the term channel noise, naming what Claude Shannon had previously identified in 1948 as the source of noise within the communication channel itself (as shown in figure 1).

So what do we take forward from the decade of noise? Two critically important concepts that can change the way we think about visual communication design – channel noise and code noise. Channel noise makes a visual message hard to perceive, code noise makes something that may be perfectly perceived, hard to understand. Think of the various ways channel noise and code noise can be generated in visual communication, making messages unclear. Designers need to be aware of these phenomena.

Have you heard of these concepts before? Discuss these ideas – channel noise and code noise – with other designers. Don’t you think that if we managed and reduced visual forms of channel noise and code noise, designers would create more effective visual messages? Don’t you think these simple concepts help clarify our goals in visual communication?

[1] Gleick, J. (2011). The information: A history, a theory, a flood. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

[2] Shannon, C. E. (1948). A mathematical theory of communication. The Bell System Technical Journal, 27

(3), 379-423. [3] Shannon, C. E., Weaver, W. (1998). The mathematical theory of communication. Urbana and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press. (Original work published 1949).

[4] Schramm, W. (1954). How communication works. In W. Schramm (Ed.), The process and effects of mass communication, Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

[5] Hockett, C. F. (1958). A course in modern linguistics. New York, NY: MacMillan.

Share this

Posted in theory. Leave a comment.