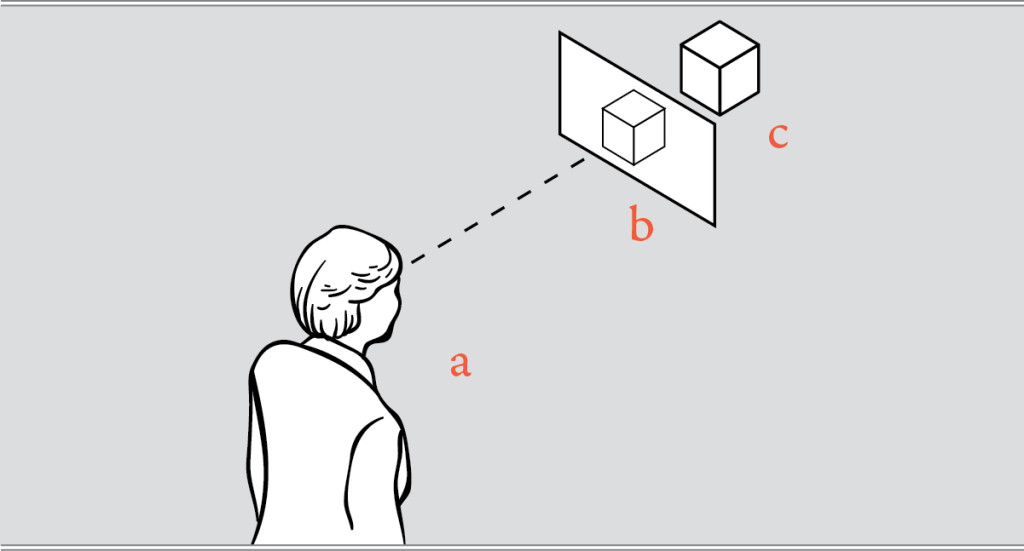

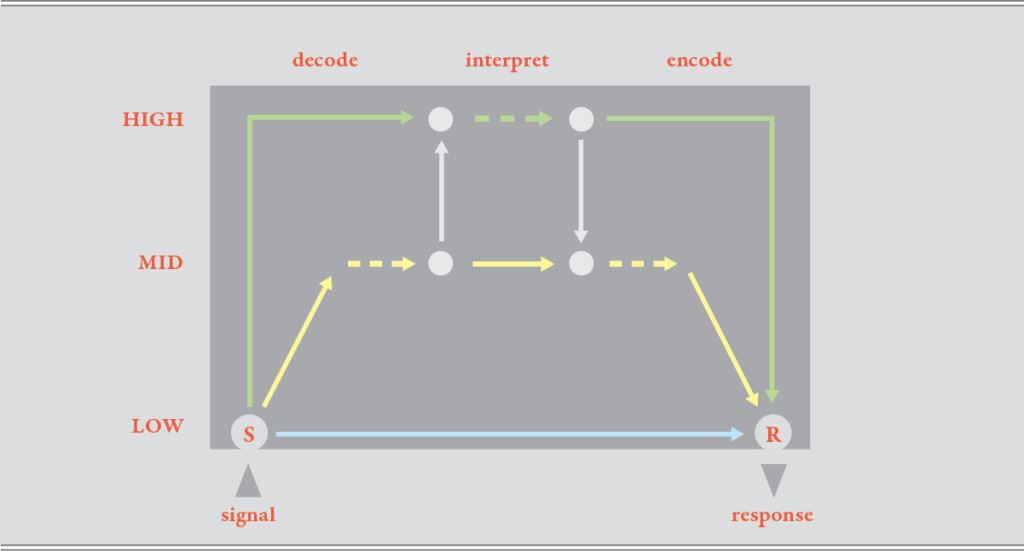

In post 1, we discussed how visual information is sent to a message receiver (a), not from the information source (c), but by the message designer who intervenes, assembling the visual message (b) on the information source’s behalf (see figure 1). We could also say this in another way – that the visual communication designer encodes the message, so it can be decoded by the message receiver (Is this what visual communication designers think they are doing? Encoding messages?). Sorry to deflate any egos, but the visual communication designer is usually not the author, but the author’s advocate.

Figure 1

The designer’s encoded message does not get decoded and ascribed meaning until it reaches the mind of the message receiver, and this begs a critical question…

Shouldn’t visual designers be well educated in cognitive science and psychology? How could anybody pretend to be expert at encoding visual messages without having some understanding of the mental processes involved in decoding these messages? But wait. I never studied psychology or cognitive science before I started my professional design career. How about you?

I am not implying a visual communication designer needs a degree in psychology, but maybe the discipline of Visual Communication Design needs to build its own fundamental theory that incorporates concepts and theories derived from cognitive science and psychology. These could inform visual communication designers of the mental processes involved in decoding their visual messages.

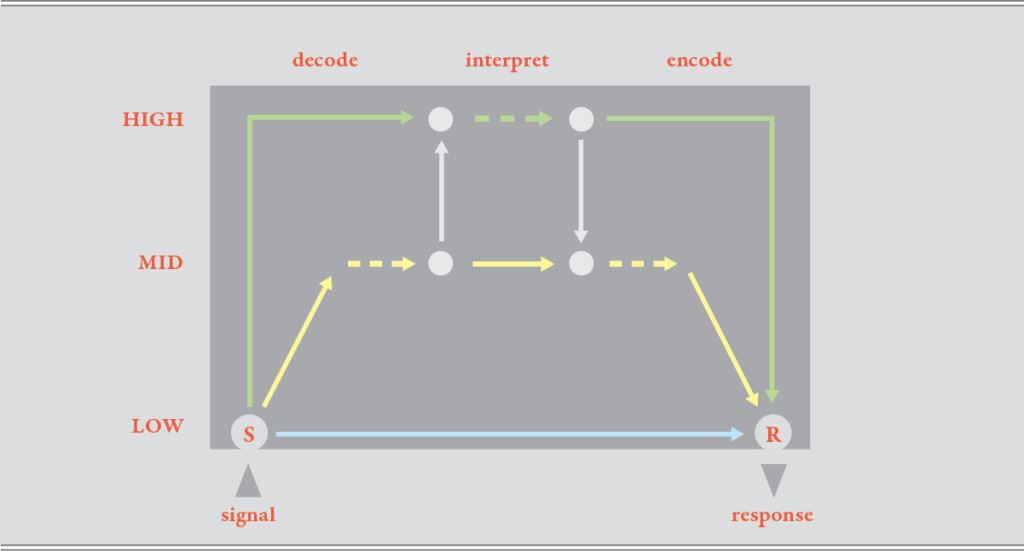

A simplified diagram of the brain’s mental processing levels, based on the concepts of the American psychologist Charles Osgood, is shown in figure 2 [1]. It illustrates several levels of mental processing that can be specifically addressed through visual design.

Figure 2: Mental processing levels

(adapted from Schramm, 1954, p11)

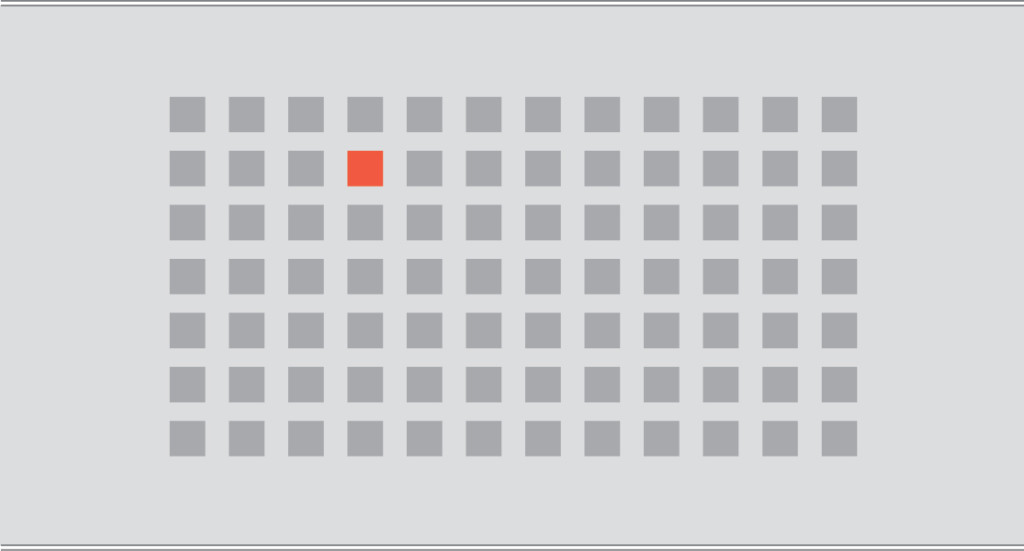

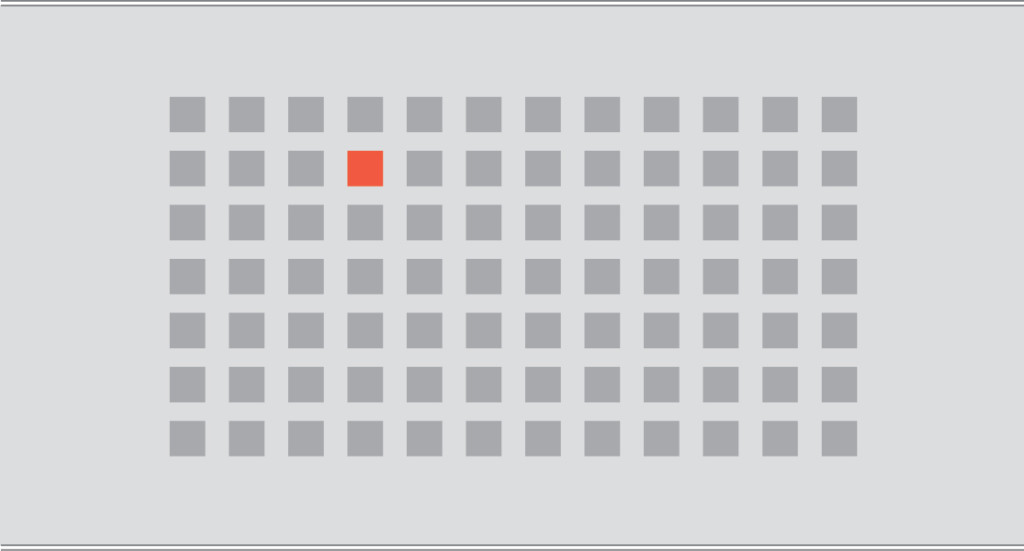

The first level of mental processing is purely perception-based, and is illustrated by the blue route, where the brain receives a stimulus and automatically reacts, such as when someone surprises you and you jump. This is also known as pre attentive message processing[2], and is illustrated, in a visual way, in figure 3 (below). See how long it takes you to notice a difference between elements in this figure. It is actually, immediate. Such visual distinctions are instantaneous and therefor termed preattentive. This means they are perceived before attention is consciously granted by the viewer.

The second level of mental processing is shown in figure 2 (above) by the yellow route, where a medium degree of mental processing is involved, such as when someone calls out your name, and you reply, “yes”. More thorough mental processing is required for the green route, where the receiver must consider the meaning of a received message by decoding it, shown here in the central top “interpretation” stage.

Figure 3: Preattentive visual perception

So, this is important to visual designers – because figure 2 implies that complex messages do not simply arrive intact. They must be accurately decoded to be understood. The diagram also suggests that speaking to the correct levels of mental processing may make message decoding easier for the brain. Thus, some aspects of a visual message may be communicated through subconscious visual means, while others should be designed to be processed at higher levels. Not bad insight for a 60-year old diagram.

So the point is that different visual design elements or combinations affect the brain differently. Some are processed without conscious thought, while others must be accurately decoded and interpreted carefully. Visual communication designers should direct their designs to the correct mental processing levels of their message receivers to make their messages easy to understand. But how?

It is important for designers to know the best ways to visually approach each mental processing level. We must know what kinds of information can be communicated to the preattentive mind, and what kinds need higher processing. I would suggest that our aim is to communicate as much information as possible to the lower processing levels, and to reduce the amount of information that needs to be “figured out”. This will increase both our rate, and success, of information transfer.

Simply stated, future designers armed with sufficient knowledge of cognitive processing can maximize the effectiveness of their visual communication design, changing visual communication design – for the better.

[1] Schramm, W. (1954). How communication works. In W. Schramm (Ed.), The process and effects of mass communication, pp. 3-26. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

[2] Ware, C. (2013). Information visualization: Perception for design (3rd ed.). Waltham, MA: Morgan Kaufmann.

Share this

Posted in theory. Leave a comment.